[at Preventers HQ]

[at Preventers HQ]

Noin, about Wufei: Are we really going to let Sally keep that?

Une: I mean, we kept Zechs.

More Posts from Goneau2xr and Others

[at Preventers HQ]

Wufei: I prevented a murder today.

Sally: Really? I’m so glad you’re finally taking to this job! How did you do it?

Wufei, glaring at Zechs: Self control.

Writing Traumatic Injuries References

So, pretty frequently writers screw up when they write about injuries. People are clonked over the head, pass out for hours, and wake up with just a headache… Eragon breaks his wrist and it’s just fine within days… Wounds heal with nary a scar, ever…

I’m aiming to fix that.

Here are over 100 links covering just about every facet of traumatic injuries (physical, psychological, long-term), focusing mainly on burns, concussions, fractures, and lacerations. Now you can beat up your characters properly!

General resources

WebMD

Mayo Clinic first aid

Mayo Clinic diseases

First Aid

PubMed: The source for biomedical literature

Diagrams: Veins (towards heart), arteries (away from heart) bones, nervous system, brain

Burns

General overview: Includes degrees

Burn severity: Including how to estimate body area affected

Burn treatment: 1st, 2nd, and 3rd degrees

Smoke inhalation

Smoke inhalation treatment

Chemical burns

Hot tar burns

Sunburns

Incisions and Lacerations

Essentials of skin laceration repair (including stitching techniques)

When to stitch (Journal article—Doctors apparently usually go by experience on this)

More about when to stitch (Simple guide for moms)

Basic wound treatment

Incision vs. laceration: Most of the time (including in medical literature) they’re used synonymously, but eh.

Types of lacerations: Page has links to some particularly graphic images—beware!

How to stop bleeding: 1, 2, 3

Puncture wounds: Including a bit about what sort of wounds are most likely to become infected

More about puncture wounds

Wound assessment: A huge amount of information, including what the color of the flesh indicates, different kinds of things that ooze from a wound, and so much more.

Home treatment of gunshot wound, also basics More about gunshot wounds, including medical procedures

Tourniquet use: Controversy around it, latest research

Location pain chart: Originally intended for tattoo pain, but pretty accurate for cuts

General note: Deeper=more serious. Elevate wounded limb so that gravity draws blood towards heart. Scalp wounds also bleed a lot but tend to be superficial. If it’s dirty, risk infection. If it hits the digestive system and you don’t die immediately, infection’ll probably kill you. Don’t forget the possibility of tetanus! If a wound is positioned such that movement would cause the wound to gape open (i.e. horizontally across the knee) it’s harder to keep it closed and may take longer for it to heal.

Broken bones

Types of fractures

Setting a broken bone when no doctor is available

Healing time of common fractures

Broken wrists

Broken ankles/feet

Fractured vertebrae: Neck (1, 2), back

Types of casts

Splints

Fracture complications

Broken noses

Broken digits: Fingers and toes

General notes: If it’s a compound fracture (bone poking through) good luck fixing it on your own. If the bone is in multiple pieces, surgery is necessary to fix it—probably can’t reduce (“set”) it from the outside. Older people heal more slowly. It’s possible for bones to “heal” crooked and cause long-term problems and joint pain. Consider damage to nearby nerves, muscle, and blood vessels.

Concussions

General overview

Types of concussions 1, 2

Concussion complications

Mild Brain Injuries: The next step up from most severe type of concussion, Grade 3

Post-concussion syndrome

Second impact syndrome: When a second blow delivered before recovering from the initial concussion has catastrophic effects. Apparently rare.

Recovering from a concussion

Symptoms: Scroll about halfway down the page for the most severe symptoms

Whiplash

General notes: If you pass out, even for a few seconds, it’s serious. If you have multiple concussions over a lifetime, they will be progressively more serious. Symptoms can linger for a long time.

Character reaction:

Shock (general)

Physical shock: 1, 2

Fight-or-flight response: 1, 2

Long-term emotional trauma: 1 (Includes symptoms), 2

First aid for emotional trauma

Treatment (drugs)

WebMD painkiller guide

Treatment (herbs)

1, 2, 3, 4

Miscellany

Snake bites: No, you don’t suck the venom out or apply tourniquettes

Frostbite

Frostbite treatment

Severe frostbite treatment

When frostbite sets in: A handy chart for how long your characters have outside at various temperatures and wind speeds before they get frostbitten

First aid myths: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Includes the ones about buttering burns and putting snow on frostbite.

Poisons: Why inducing vomiting is a bad idea

Poisonous plants

Dislocations: Symptoms 1, 2; treatment. General notes: Repeated dislocations of same joint may lead to permanent tissue damage and may cause or be symptomatic of weakened ligaments. Docs recommend against trying to reduce (put back) dislocated joint on your own, though information about how to do it is easily found online.

Muscular strains

Joint sprain

Resuscitation after near-drowning: 1, 2

Current CPR practices: We don’t do mouth-to-mouth anymore.

The DSM IV, for all your mental illness needs.

Electrical shock

Human response to electrical shock: Includes handy-dandy voltage chart

Length of contact needed at different voltages to cause injury

Evaluation protocol for electric shock injury

Neurological complications

Electrical and lightning injury

Cardiac complications

Delayed effects and a good general summary

Acquired savant syndrome: Brain injuries (including a lightning strike) triggering development of amazing artistic and other abilities

Please don’t repost! You can find the original document (also created by me) here.

Enlisted Ranks: Army

There’s nothing I hate more than a story that didn’t even try to get its ranks right. Why is a major giving orders to a colonel? Why is a first sergeant working with a bunch of fuzzies? Why the hell did you just call the sergeant major ‘sir’?

Military ranks are different across the branches, but if your story features the U.S. Army, here’s a breakdown of enlisted ranks and rank etiquette. (other branches coming soon!)

Basics Ranks in the army follow a numerical pattern, so if you’re ever not quite sure what the name of the rank higher is, you can reference them by nomenclature. E-series: E stands for enlisted. This refers to soldiers from private to sergeant major. O-series: O stands for officer. This refers to soldiers from second lieutenant to general. O-series post coming soon! W-series: W stands for warrant officer. This refers to soldiers from warrant officer 1 to chief warrant officer 5. W-series post coming soon! In ACUs, (army combat uniform) the rank is worn in the center of the chest via a velcro patch. In class-A uniforms, the rank is worn on the shoulder. Each pay grade earns slightly more per month than the one before it. Officers make significantly more money per month than enlisted. Time in service also affects pay, meaning a sergeant who’s been in six years will make more than a staff sergeant who’s been in three years.

E-1: Private Most people who enlist come in at E-1 unless they were in JROTC, have a college degree, or performed some other feat with their recruiters prior to enlisting i.e. volunteer work, good P.T. scores, etc. This is the lowest pay grade and has no rank. Soldiers who are E-1s do not wear a rank. also known as: PV1, fuzzy (because they wear no velcro rank, there’s a patch of bare fuzz in the middle of their uniform. You can buy a patch to cover it.) Title: Private, PV1 E-2: Private Yes, there are two ranks by the name of private. You reach E-2 automatically after six months of enlistment. If you enroll in the Delayed Entry Program or have an acceptable P.T. card with your recruiter, you can enlist as an E-2 instead of an E-1. At E-2, you more or less have no more power than an E-1. also known as : PV2 Title: Private, PV2

E-3: Private First Class The final “private” class. You reach E-3 automatically after 12 months of enlistment, assuming you’ve been an E-2 for at least four months. If you were in JROTC for four years, you enter automatically at this rank. This rank still doesn’t have much power, but may be put in charge of other privates and may assist their team leader with tasks, and on occasion may be a team leader themselves. also known as : PFC Title: Private, PFC. E-4: Specialist/Corporal The last “junior enlisted” class. You reach specialist automatically after 24 months of enlistment, assuming you’ve been a PFC for at least six months. If you enlist with a completed four year college degree, you can start out as an E-4 instead of an E-1. Specialists tend to be team leaders and may be in charge of other specialists and privates. When no NCOs are present, the senior specialist is in charge.

Corporal, while technically the same pay grade as specialist, is actually an essentially higher rank. It’s a special rank only bestowed on those who are in leadership positions and are awaiting the appropriate time in service/time in grade to be promoted to sergeant. Corporals are considered NCOs while specialists are considered junior enlisted. Strictly speaking corporals and specialists are the same rank, but in most situations, corporals out rank specialists. also known as: shamshields, (specialist only) SPC, CPL Title: Specialist, Corporal —

Intermission!

Man, all of that text is boring. Let’s break it up a bit with some rank etiquette, shall we?

• Lower enlisted (E-1 thru E-4) tend to call each other by their surname regardless of rank. Even an E-1 will probably be calling a specialist just by their name. The exception is Corporals, who are considered NCOs and are referred to by rank.

• E-5 and above are referred to as “NCOs,” or non-commissioned officers.

• NCOs with similar ranks might call each other by their surnames and will call lower enlisted by their surnames. When discussing another NCO with a lower enlisted, they will use that NCO’s proper rank. So a sergeant speaking to a PFC will say “Sergeant Smith needs you,” not “Smith needs you.” Freshly promoted sergeants who still hang out with lower enlisted might not mind their friends calling them their surnames in private, but formally and professionally they’re expected to address their senior properly.

• Lower enlisted ranks are often called “joes,” especially when an NCO is addressing another NCO about their squad or platoon. “Have your joes had chow yet?” = “Have the soldiers directly under your command eaten yet?”

• It’s considered inappropriate for lower enlisted to hang out with NCOs and it’s discouraged, especially in the work place.

Are you all rested up? Great! Let’s get back to the ranks.

—

E-5: Sergeant

Finally: the NCO ranks! Unlike the previous ranks, you cannot automatically rank up to sergeant. You must attend special courses and be seen by a promotion board where you’ll be expected to recite the NCO creed and have knowledge appropriate for an non-commissioned officer. From this rank on, lower-ranked soldiers will refer to you as “sergeant” and you will likely be a squad leader or in another leadership position.

• Lower enlisted do NOT refer to sergeants by their surname unless it is paired with their rank. “Sergeant Smith,” not just “Smith,” or your private will be doing a lot of push-ups.

• No one calls them “Sarge.” Like… just don’t do it friends.

• Some pronounce sergeant in such a way it sounds as though the g is dropped entirely. Ser-eant, or phonetically, “saarnt.”

also known as: SGT

Title: Sergeant

E-6: Staff Sergeant

Sergeant Plus. You probably will have similar responsibilities to an E-5, meaning probably a squad leader unless you need to fill in for a platoon sergeant. Don’t misunderstand; in lower enlisted ranks, private and private first class aren’t that much of a difference. E-5 and E-6 are a definite difference though. It is acceptable to call an E-6 either “sergeant” or “sergeant (name)” instead of staff sergeant.

also known as: SSG

Title: Sergeant

E-7: Sergeant First Class

At this point the ranks become known as “senior NCO.” E-7 and above cannot be demoted by normal means. It actually requires a court martial or congressional approval to demote an E-7. Like, it’s surprisingly hard to demote people after this point. I once knew an E-7 who got busted with a DUI and STILL didn’t lose his rank.

Anyway, it’s still appropriate to call an E-7 “sergeant” or “sergeant (name)” instead of sergeant first class. SFCs may be platoon sergeants or in some circumstances may hold a first sergeant position. While positioned as a first sergeant, they should be referred to as “first sergeant.” Unless you work at battalion level or higher, this is probably the highest NCO rank you’ll interact with regularly, and in some cases interacting with an E-7 can be as big a deal as interacting with an E-8.

also known as: SFC

Title: Sergeant

E-8: First Sergeant/Master Sergeant

Another dual-rank. First sergeants are the NCO in charge of a company and are usually the highest ranking NCO soldiers will interact with regularly. They run the company alongside the company commander. All NCOs answer to them and most beginning of the day and end of the day formations will be initiated and ended with them. It is only appropriate to refer to a first sergeant as “first sergeant” or “first sergeant (name).” Do not just call them “sergeant.”

Master sergeants are E-8s who are not in a first sergeant position. Typically these people wind up working in offices in battalion or brigade. It’s only appropriate to refer to a master sergeant as “master sergeant” or “master sergeant (name).”

also known as: 1SG, FSG, (first sergeant only) MSG (master sergeant only)

Titles: First Sergeant, Master Sergeant.

E-9: Sergeant Major or Command Sergeant Major

We finally reach the end of the list: Sergeant Major, the highest ranking NCO. Sergeant Majors will be found at battalion level and higher. Command Sergeant Majors are those that hold a leadership position in a battalion, brigade, etc, like first sergeant vs master sergeant. It is appropriate to refer to E-9s as “sergeant major” or “sergeant major (name).” Typically, a command sergeant major will be referred to AS command sergeant major.

In the U.S., the plural form of sergeant major is “sergeants major.” Outside the U.S., “sergeant majors” can be correct.

also known as: SGM, CSM

Title: Sergeant Major

Now, for the most important announcement:

Soldiers NEVER, and I mean NEVER, refer to an NCO as “sir” or “ma’am.” Forget what the movies tell you; if your first sergeant is chewing you out, you do not say “ma’am, yes ma’am!” You’ll earn yourself some push-ups and some cleaning duty and probably a counseling. Do you see how under every rank I’ve provided a “title” section? That’s how your soldiers address that rank. Period. The only people who get called “sir” and “ma’am” are civilians and officers. Cannot tell you how many movies I’ve rolled my eyes into my skull because some snot-nosed private is calling their squad leader “sir.” Please cease this immediately. Thank you.

That’s all for scriptsoldier’s rank breakdown of enlisted ranks! Stay tuned for our breakdown of officers, warrant officers, and how your rank affects your standing in your unit!

With credit to @afro-elf

OZ Judge: For your crimes, we sentence you to 68 years in prison.

Duo: Can you…

Duo: Can you add one more year?

Trowa, in the background, undercover: [sighs]

How To: Develop Your Characters

I think we’ve all been in the situation where we want to write about a specific character but have no idea how to approach it. For some reason, despite them being your own character, you have no idea how they would act or what they would say in a certain situation. Sometimes, if you even write about your character(s) at all, when you read it back they seem fake or 2-Dimensional. Unrealistic, if you’d prefer.

In this post, I am going to give you some exercises to get past hollow characters and help develop your writing.

1) Empty Their Pockets

Pretty simple. Think of what your characters would have in their pockets on a day-to-day basis. It doesn’t have to be anything super extraordinary, of course. Just start writing some everyday items down and think about whether your character would have these items in their pockets.

Let’s take a look at one I did for my characters earlier. (sorry that just sounded like something from Blue Peter)

For example:

Character A’s Pockets Contained:

pack of gum, empty pack of cigarettes, library card, NOKIA brick phone

So, here a few things you can tell about Character A simply through the items in their pockets. They visit the library often, meaning that they probably have a high interest in reading (this also could be a sign of intelligence). Judging by the fact Character A has both a pack of gum and cigarettes this could indicate a potential smoking habit, chewing gum is a known way for helping people quit smoking. The pack of cigarettes could show that they are not very good at restricting themselves and could in fact be addicted and finding it hard to cope with smoking. Finally, the NOKIA brick phone shows how they may want to feel connected to people or want to allow their friends/family members/whoever to be able to contact them but have no desire to get the latest model of phone or perhaps believe that having such a device would distract them unnecessarily.

When doing this exercise, think about key objects which portray certain details about your character! Try not to overthink it too much, write whatever comes to mind and put it down on the page! After writing down a couple objects, go back through them and feel free to edit out items you think are unnecessary or add items which you think would suit the character.

2) Go Through Their Daily Routine

Again, another easily explained exercise. Go through a regular day in your character’s life, try and do this exercise as if it was happening before whatever events occur in your story or novel. This way it makes it easier to understand your character before they met a secondary character in the novel or before whatever events happened in your writing which may affect their routine. You don’t need to include every single detail in your description, just brief notes or key events which occur during their day would be fine. You can make it as short or as long as you wish, maybe don’t just do it for one day in your character’s week perhaps do it for multiple days.

Does their routine change during the week? What time do they wake up? What time do they go to sleep? Are they punctual with going to work? Do they do any other activities outside their day-job? These are the kind of things you may want to ask yourself when writing it.

3) Give Them Fears/Phobias

Everyone fears something: whether it be a phobia of spiders or oblivion, everyone has a fear. Giving your character a phobia makes them seem more realistic, it allows your reader to easily relate to your character.

However, just having a phobia for the sake of it doesn’t help develop your character at all. If you give them a terrible phobia of snakes and they come across a snake and suddenly within moments are able to get over their fear just like that, it’s not a phobia. It’s more of a mild inconvenience than anything else. The reader needs to feel convinced by their fears, they would feel more dissatisfied with your writing if they felt the character could dismiss anything and everything than knowing them being confronted by their fears could be a possible problem. Besides, it would give them no reason to motivate or encourage the character if they knew it was impossible for them to be defeated by anything. Still, this does not mean that your character has to be destroyed by their fear. There is a very big difference between simply dismissing your character’s fear and perhaps overcoming it in the future.

An easy way to write your character possibly overcoming their fear in the future is that when they first encounter that fear, add an element of chance or fate into it. For example, if a character were to move to get away from the creature which may be coming towards them; in the process of getting up, they could slip which could cause their legs to lash out towards the creature. The sudden movement may just be enough to scare the creature away, this way it does not appear to the reader as ridiculous or uncharacteristic courage but instead accidental bravery. This sudden revelation that the character’s horrible fear may not be as all powerful as they first thought could be the first step for them to slowly overcome that fear.

Don’t believe me? Let’s think about this for a moment. Imagine your character, let’s call them the Protagonist™, is stuck in a terrible situation. It doesn’t matter what the situation is but let’s say it’s something which involves them being trapped in a room with a snake. I’m going to give you two examples, both involving the same situation.

Example #1: Protagonist watched with wide eyes as the snake slowly slithered towards them. The snake paused for a moment, it hissed lowly as it waited for Protagonist to move, waiting for the right moment to strike. Not hesitating for a single moment, they suddenly realised how dire the situation was and jumped to their feet. Their heart pumping wildly as their body was filled with adrenaline, they were terrified yet they had to do something. Protagonist grabbed the nearest thing to them and stepped towards the snake.

“Get away!” They threatened, “Get away!”

Example #2:

Protagonist watched with wide eyes as the snake slowly slithered towards them. The snake paused for a moment, it hissed lowly as it waited for Protagonist to move, waiting for the right moment to strike. The blood in Protagonist’s veins ran cold as the snake grew closer and closer, Protagonist couldn’t move. They begged and screamed on the inside to move away, to get away as far as possible. They had lost all control of their movement, their fear had consumed them. They were frozen to the spot and could only watch as the snake widened it’s jaw, ready to bite down on it’s prey. It widened it’s jaw once, twice - suddenly, Protagonist gained back their instincts. Fleeing seemed like the only realistic option and seconds before the snake could chomp down on their ankle, Protagonist stumbled to their feet. They stumbled backwards into a puddle of water which had pooled behind them and their ankle rolled as they slipped, their legs accidentally lashing out towards the predator. The snake recoiled backwards in shock before deciding that the risk wasn’t worth it: it quickly retreated back to it’s nest, disappearing from Protagonist’s view.

Now, hopefully you see what I mean. I think we can all agree that the second example is a lot better than the first one.

4) Create Their Flaws/Bad Habits

No one is perfect, this includes your characters.

If you’re finding it challenging to think of any flaws, try to think of some bad habits. It doesn’t have to be anything so terribly bad that’s it’s illegal. Think simple when it comes to this exercise. It can range from anything between chewing their nails to swearing.

It might help to try and develop these bad habits into possible flaws or weaknesses. If your character keeps biting their nails that might be a sign of nervousness or anxiety. So, creating bad habits might be a good way to show a certain trait your character may possess.

Flaws are important as well. Let’s be realistic, if no character had any flaws then every single book we read would be filled with a bunch of characters which are exactly the same. Besides, what’s a hero without it’s villain?

So, to give you a few ideas, let’s go back to superheroes. Maybe a hero is so set on doing the right thing that they lose sight of what they want? Perhaps it gets to a certain point where they can’t handle that hollow feeling inside of them that they grow arrogant, selfish or even stubborn? There’s a story for you right there.

Not only that, by giving your characters flaws it is possible that you could work that into your story somehow. This way, not only will you get to show off your amazing character development, but it could also be an exciting point in your storyline.

Write down some ideas, think of flawed personality traits and just write them down! Try to write down at least five straight off the bat, for each one you don’t like you should think about why it doesn’t suit your character. You’re bound to find one flaw you’re happy with!

5) Write Some Scenarios

Now that you’ve developed your characters, go ahead and write them in your story! If you think you still need a bit of practice, try writing something about them being in a certain scenario. It could be anything from ordering their favourite coffee to being trapped in a prison: just write it! Try not to think about it too much, just do whatever feels write (I unintentionally made that pun but i’m not deleting it).

It doesn’t have to be long either, just a couple paragraphs would be fine. Try to focus on body movements and interior thoughts, it would be ideal if your character was on their own in the situation: that way you can get to know the character on their own a lot better. No other characters means no distractions. It’s just you, the wonderful author, and your character - there is an endless amount of possibilities for you!

Have faith in yourself too! Nobody knows your brilliantly developed characters better than you do, so here’s your chance to show them off! If you’d like a second opinion, write something about them and give it to a friend/parent/random stranger etc. to read! If they don’t want to, make them read it anyway!

I hope this helps you all in developing your characters!

Happy writing!

- jess

ANYA TAYLOR-JOY 26th Annual Critics’ Choice Awards › March 7, 2021

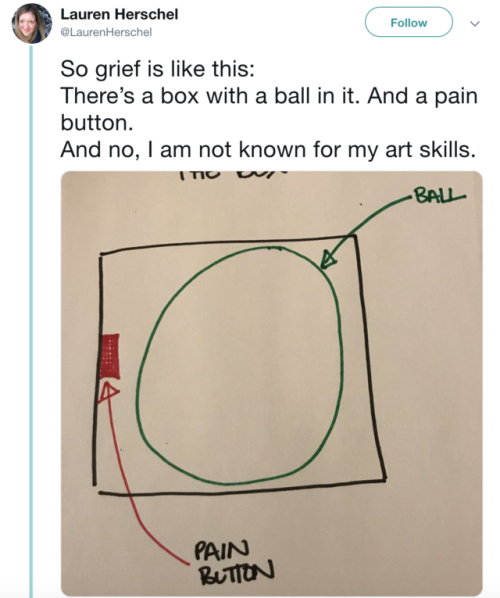

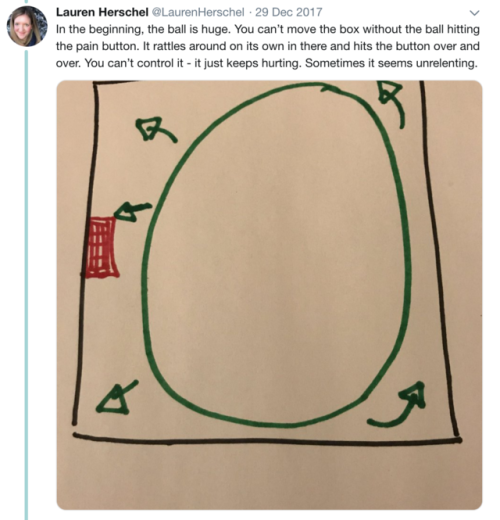

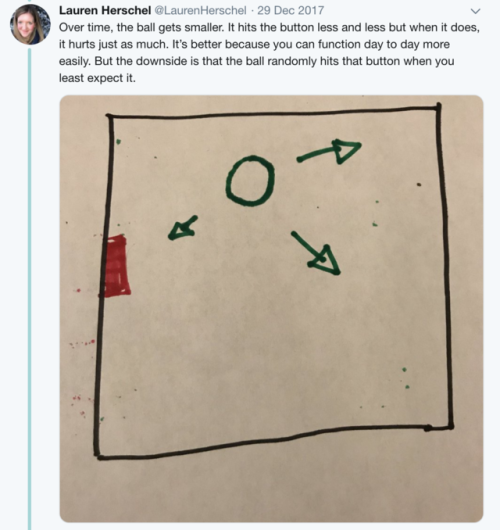

This is the most accurate description I’ve ever found, thought it was worth spreading ❀

OZ Soldier: Turn around!

Duo, singing: Every now and then I get a little bit lonely and you’re never comin’ round~

OZ Soldier: TURN AROUND!!

Duo: Every now an- [gets tased]

-

yui-hibari liked this · 1 year ago

yui-hibari liked this · 1 year ago -

thedragonchilde liked this · 5 years ago

thedragonchilde liked this · 5 years ago -

goneau2xr reblogged this · 5 years ago

goneau2xr reblogged this · 5 years ago -

theauthorityvol1 reblogged this · 6 years ago

theauthorityvol1 reblogged this · 6 years ago -

a-locket-s-tale liked this · 6 years ago

a-locket-s-tale liked this · 6 years ago -

universal-ren-kin reblogged this · 6 years ago

universal-ren-kin reblogged this · 6 years ago -

oceans-pebble liked this · 6 years ago

oceans-pebble liked this · 6 years ago -

stoic-rose reblogged this · 6 years ago

stoic-rose reblogged this · 6 years ago -

stoic-rose liked this · 6 years ago

stoic-rose liked this · 6 years ago -

cosmostar liked this · 6 years ago

cosmostar liked this · 6 years ago -

noirangetrois reblogged this · 6 years ago

noirangetrois reblogged this · 6 years ago -

bryony-rebb liked this · 6 years ago

bryony-rebb liked this · 6 years ago -

strea-ultimea liked this · 6 years ago

strea-ultimea liked this · 6 years ago -

vegalume reblogged this · 6 years ago

vegalume reblogged this · 6 years ago -

vegalume liked this · 6 years ago

vegalume liked this · 6 years ago -

ashke-leshay liked this · 6 years ago

ashke-leshay liked this · 6 years ago -

godofalleyeteeth liked this · 6 years ago

godofalleyeteeth liked this · 6 years ago -

jovian-dragoon liked this · 6 years ago

jovian-dragoon liked this · 6 years ago -

tinyearthquakepatrol liked this · 6 years ago

tinyearthquakepatrol liked this · 6 years ago -

terrablaze514 liked this · 6 years ago

terrablaze514 liked this · 6 years ago -

wolvesandgundams liked this · 6 years ago

wolvesandgundams liked this · 6 years ago -

chaoslovesdestruction reblogged this · 6 years ago

chaoslovesdestruction reblogged this · 6 years ago -

chaoslovesdestruction liked this · 6 years ago

chaoslovesdestruction liked this · 6 years ago -

kirinjaegeste reblogged this · 6 years ago

kirinjaegeste reblogged this · 6 years ago -

kirinjaegeste liked this · 6 years ago

kirinjaegeste liked this · 6 years ago -

moonfirekitsune liked this · 6 years ago

moonfirekitsune liked this · 6 years ago -

purusintellectus liked this · 6 years ago

purusintellectus liked this · 6 years ago -

seitou liked this · 6 years ago

seitou liked this · 6 years ago -

ash1102 liked this · 6 years ago

ash1102 liked this · 6 years ago -

anaranesindanarie liked this · 6 years ago

anaranesindanarie liked this · 6 years ago -

noirangetrois liked this · 6 years ago

noirangetrois liked this · 6 years ago -

deathwinglover liked this · 6 years ago

deathwinglover liked this · 6 years ago -

burningwreckage liked this · 6 years ago

burningwreckage liked this · 6 years ago -

knottybodyworker liked this · 6 years ago

knottybodyworker liked this · 6 years ago -

avengersemhwasp1 liked this · 6 years ago

avengersemhwasp1 liked this · 6 years ago -

incorrectgundamwingquotes reblogged this · 6 years ago

incorrectgundamwingquotes reblogged this · 6 years ago

Go away, there's nothing for you here. I ship Duo and Relena and you'll pry my rarepair from my cold dead hands.

259 posts