Philosophical-amoeba - Lost In Space...

More Posts from Philosophical-amoeba and Others

BHL Book Feature: The Birds of Singapore Island

Our book feature this week is The Birds of Singapore Island (1927), co-authored by John Alexander Strachey Bucknill and Frederick Nutter Chase with SciArt by Gerald Aylmer Levett-Yeats, and published by the Raffles Museum. This work is the first book on the birds of Singapore!

Our featured illustration is a Greater Racket-tailed Drongo (Dicrurus paradiseus platurus). This book is written in an informal, non-scientific style to appeal to tourists and bird enthusiasts, and the description of the Greater Racket-tailed Drongo is a good example of this writing style.

All this week, we will be sharing several of the 31 plates from The Birds of Singapore Island, which was digitized for BHL by National Library Board, Singapore. You can view all of the plates from this work in our Flickr album, and check out our blog post, which was written by Ong Eng Chuan, Senior Librarian of the National Library Board, Singapore.

Joan Beauchamp Procter: her best friend was a Komodo dragon and if that doesn’t entice you to read this, I don’t know what will

Joan Beauchamp Procter is a scientist every reptile enthusiast should admire.

Joan was an incredibly intelligent young woman who was chronically ill (and as a result of her chronic illness, physically disabled by her early thirties). Her health issues kept her from going to college, but that did not stop her from studying and keeping reptiles. She presented her first paper to the Zoological Society of London at the tender age of nineteen, and the society was so impressed that they hired her to help design their aquarium. In 1923, despite having no formal secondary education and despite being only 26 years old, she was hired as the London Zoo’s curator of reptiles. Now, that in and of itself is an awesome accomplishment, but Joan was absolutely not content to maintain the status quo. Nosiree, by the age of 26 Joan had already kept many exotic pets (including a crocodile!) and knew a thing or two about what needed to be done to improve their lives in captivity. So Joan got together with an architect, Edward Guy Dawber, and designed the world’s first building designed solely for the keeping of reptiles. She had some really, really great ideas. Her first big idea was to make the building differentially heated- different areas and enclosures would have different heat zones, instead of having the whole building heated to one warm temperature. She also set up aquarium lighting- the gallery itself was dark, with dim lights on individual enclosures to make things less stressful for the inhabitants. She also insisted on the use of special glass that didn’t filter out UVB. This meant that reptiles could synthesize vitamin D and prevented cases of MBD in her charges.

But advances in enclosure design weren’t Joan’s only contribution to reptile keeping. She was also one of the first herpetologists to study albinism in snakes- she was the first to publish an identification how albinism manifests in reptile eyes differently than in mammal eyes, and stressed the importance of making accurate color plates of reptiles during life because study specimens often lose pigmentation. She also was really hands-on with many species, including crocodiles, large constrictors, and monitor lizards. Joan had this idea that if you socialize an animal and get it used to handling, then when you need to give it a vet checkup, things tend to go a lot better. This really hadn’t been done with reptiles before. She was able to identify many unstudied diseases, thanks to her patient handling of live specimens, and by being patient and going slow, she managed to get a lot of very large, dangerous creatures to trust her. One of them (that we know of) even came to like her- a Komodo dragon named Sumbawa.

In 1928, two of the first Komodo dragons to be imported to Europe arrived at the London Zoo. One of them, named Sumbawa, came in with a nasty mouth infection. His first several months at the zoo were a steady stream of antibiotics and gentle care, and by the time he’d recovered enough for display, he had come to be tolerant of handling and human interaction. In particular, he seemed to be genuinely fond of Joan. She was their primary caretaker and wrote many of the first popular accounts of Komodo dragon behavior in captivity. While recognizing their lethal capacity, she also wrote about how smart they are and how inquisitive they could be. In her account published in The Wonders of Animal Life, she said that "they could no doubt kill one if they wished, or give a terrible bite" but also that they were “as tame as dogs and even seem to show affection.” To demonstrate this, she would take Sumbawa around on a leash and let zoo visitors interact with him. She would also hand-feed Sumbawa- pigeons and chickens were noted to be favorite food, as were eggs.

Joan died in 1931 at the age of 34. By that time she was Doctor Procter, as the University of Chicago had awarded her an honorary doctorate. Until her death, she still remained active with the Zoological Society of London- and she was still in charge of her beloved reptiles. Towards the end of her life, Joan needed a wheelchair. But that didn’t stop her from hanging out with her giant lizard friend. Sumbawa would walk out in front of the wheelchair or beside it, still on leash- she’d steer him by touching his tail. At her death, she was one of the best-known and respected herpetologists in the world, and her innovative techniques helped shape the future of reptile care.

Ancient Egypt as seen through western eyes is mostly monumental and remote, distant in time and overwhelming in scale. The earliest western illustrations and photographs of Egypt regularly emphasized size and stillness; romantic artists of the nineteenth century frequently placed people in vast desert landscapes—the figures small and insignificant, lost in the deep antiquity of an unchanging land.

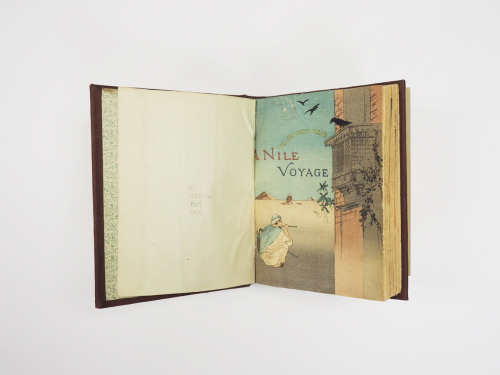

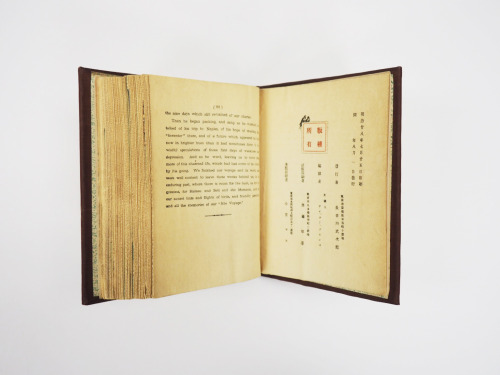

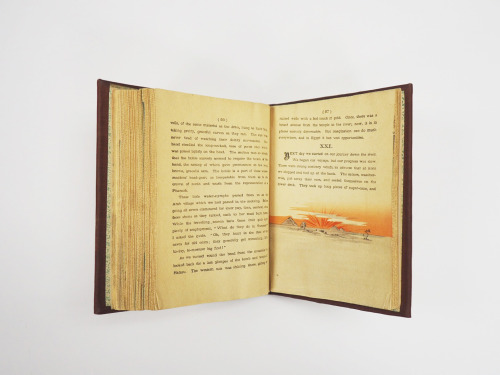

This grand vision of Egypt is so firmly fixed in western culture that discovering a different interpretation comes as a revelation. Fortunately, the Brooklyn Museum Wilbour Library of Egyptology owns a rare treasure that offers an alternate view. A Nile Voyage of Recovery, by Charles and Susan Bowles was published in Japan by Hasegawa Takejirō [長谷川武次郎 in 1896. Hasegawa was Japanese publisher active in the late nineteenth century who specialized in books in European languages, often for Japan’s tourist trade and resident foreign community, which included many English missionaries. The volume is part of the Red Cross series. During this time period, the Red Cross was active in setting up libraries and creating publications for soldiers in hospitals and recovery centers around the world.

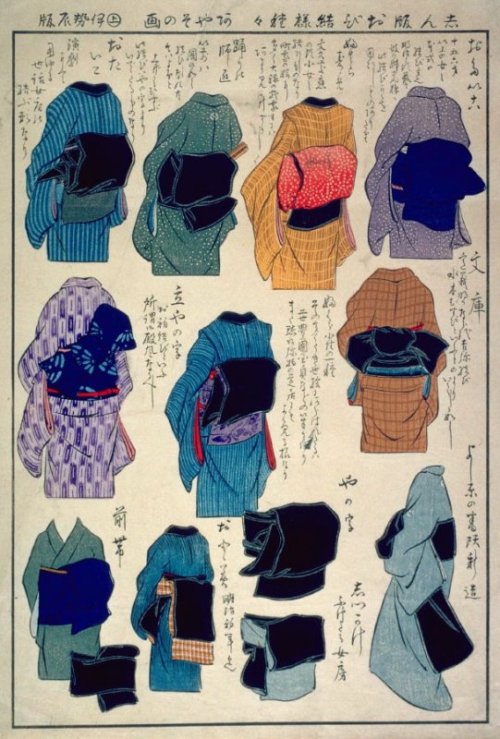

Many of Hasegawa’s early books were in the form of chirimen-bon (ちりめん本) or crêpe paper books. Chirimen, or crepe, is a Japanese textile with a soft, slightly wrinkly texture that’s often used in Japan to make kimonos, or for wrapping cloth. Hasegawa used the material to produce small, delicate books that can be held in the hand with the pages unfolding easily like fabric.

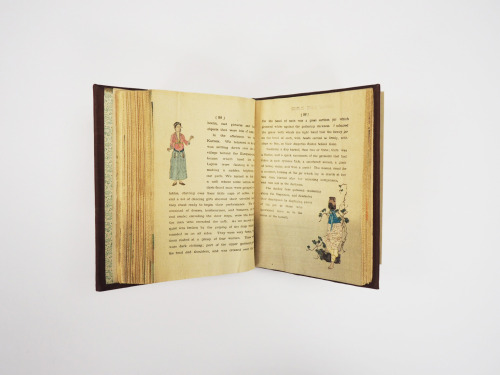

Our chirimen-bon of A Nile Voyage of Recovery is illustrated with graceful, color woodblock prints of Egyptian scenes and adorned with exquisite typography. The images are gentle and intimate, emphasizing details and delicate color. Even a portrayal of the great pyramid gives more page-room to rays of light and the sun rather than the monuments. The Sphinx does not dominate; it’s rather an integral part of the landscape.

Why study this human-scale Egypt? Because the purpose of art after all is to unsettle the conventional view—and whenever we see the world through other eyes, we see something new.

Posted by Roberta Munoz Photos by Brooke Baldeschwiler

Idempotence.

A term I’d always found intriguing, mostly because it’s such an unusual word. It’s a concept from mathematics and computer science but can be applied more generally—not that it often is. Basically, it’s an operation that, no matter how many times you do it, you’ll still get the same result, at least without doing other operations in between. A classic example would be view_your_bank_balance being idempotent, and withdraw_1000 not being idempotent.

HTs: @aidmcg and Ewan Silver who kept saying it

im putting together a couple of scottish folk mixes bc that’s what i do and im honestly curious if anyone in my country has ever been unequivocally happy about anything ever

The Okinawan Language

Anybody who has studied Japanese and Linguistics will know that Japanese is a part of the Japonic language family. For many years it was thought that Japanese was a language isolate, unrelated to any other language (Although there is some debate as to whether or not Japanese and Korean are related). Today, most linguists are in agreement that Japanese is not an isolate. The Japonic languages are split into two groups: Japanese (日本語) and its dialects, which range from standard Eastern Japanese (東日本方言) to the various dialects found on Kyūshū (九州日本方言), which are, different, to say the least. The Ryukyuan Languages (琉球語派). Which are further subdivided into Northern and Southern Ryukyuan languages. Okinawan is classified as a Northern Ryukyuan Languages. There are a total of 6 Ryukyuan languages, each with its own dialects. The Ryukyuan languages exist on a continuum, somebody who speaks Okinawan will have a more difficult time understanding the Yonaguni Language, which is spoken on Japan’s southernmost populated island. Japanese and Okinawan (I am using the Naha dialect of Okinawan because it was the standard language of the Ryukyu Kingdom), are not intelligible. Calling Okinawan a dialect of Japanese is akin to calling Dutch a dialect of English. It is demonstrably false. Furthermore, there is an actual Okinawan dialect of Japanese, which borrows elements from the Okinawan language and infuses it with Japanese. So, where did the Ryukyuan languages come from? This is a question that goes hand in hand with theories about where Ryukyuan people come from. George Kerr, author of Okinawan: The History of an Island People (An old book, but necessary read if you’re interested in Okinawa), theorised that Ryukyuans and Japanese split from the same population, with one group going east to Japan from Korea, whilst the other traveled south to the Ryukyu Islands. “In the language of the Okinawan country people today the north is referred to as nishi, which Iha Fuyu (An Okinawn scholar) derives from inishi (’the past’ or ‘behind’), whereas the Japanese speak of the west as nishi. Iha suggests that in both instances there is preserved an immemorial sense of the direction from which migration took place into the sea islands.” (For those curious, the Okinawan word for ‘west’ is いり [iri]). But, it must be stated that there are multiple theories as to where Ryukyuan and Japanese people came from, some say South-East Asia, some say North Asia, via Korea, some say that it is a mixture of the two. However, this post is solely about language, and whilst the relation between nishi in both languages is intriguing, it is hardly conclusive. With that said, the notion that Proto-Japonic was spoken by migrants from southern Korea is somewhat supported by a number of toponyms that may be of Gaya origin (Or of earlier, unattested origins). However, it also must be said, that such links were used to justify Japanese imperialism in Korea. Yeah, when it comes to Japan and Korea, and their origins, it’s a minefield. What we do know is that a Proto-Japonic language was spoken around Kyūshū, and that it gradually spread throughout Japan and the Ryukyu Islands. The question of when this happened is debatable. Some scholars say between the 2nd and 6th century, others say between the 8th and 9th centuries. The crucial issue here, is the period in which proto-Ryukyuan separated from mainland Japanese. “The crucial issue here is that the period during which the proto-Ryukyuan separated(in terms of historical linguistics) from other Japonic languages do not necessarily coincide with the period during which the proto-Ryukyuan speakers actually settled on the Ryūkyū Islands.That is, it is possible that the proto-Ryukyuan was spoken on south Kyūshū for some time and the proto-Ryukyuan speakers then moved southward to arrive eventually in the Ryūkyū Islands.” This is a theory supported by Iha Fuyu who claimed that the first settlers on Amami were fishermen from Kyūshū. This opens up two possibilities, the first is that ‘Proto-Ryukyuan’ split from ‘Proto-Japonic’, the other is that it split from ‘Old-Japanese’. As we’ll see further, Okinawan actually shares many features with Old Japanese, although these features may have existed before Old-Japanese was spoken. So, what does Okinawan look like? Well, to speakers of Japanese it is recognisable in a few ways. The sentence structure is essentially the same, with a focus on particles, pitch accent, and a subject-object-verb word order. Like Old Japanese, there is a distinction between the terminal form ( 終止形 ) and the attributive form ( 連体形 ). Okinawan also maintains the nominative function of nu ぬ (Japanese: no の). It also retains the sounds ‘wi’ ‘we’ and ‘wo’, which don’t exist in Japanese anymore. Other sounds that don’t exist in Japanese include ‘fa’ ‘fe’ ‘fi’ ‘tu’ and ‘ti’. Some very basic words include: はいさい (Hello, still used in Okinawan Japanese) にふぇーでーびる (Thank you) うちなー (Okinawa) 沖縄口 (Uchinaa-guchi is the word for Okinawan) めんそーれー (Welcome) やまとぅ (Japan, a cognate of やまと, the poetic name for ‘Japan’) Lots of Okinawan can be translated into Japanese word for word. For example, a simple sentence, “Let’s go by bus” バスで行こう (I know, I’m being a little informal haha!) バスっし行ちゃびら (Basu sshi ichabira). As you can see, both sentences are structured the same way. Both have the same loanword for ‘bus’, and both have a particle used to indicate the means by which something is achieved, ‘で’ in Japanese, is ‘っし’ in Okinawan. Another example sentence, “My Japanese isn’t as good as his” 彼より日本語が上手ではない (Kare yori nihon-go ga jouzu dewanai). 彼やか大和口ぬ上手やあらん (Ari yaka yamatu-guchi nu jooji yaaran). Again, they are structured the same way (One important thing to remember about Okinawan romanisation is that long vowels are represented with ‘oo’ ‘aa’ etc. ‘oo’ is pronounced the same as ‘ou’). Of course, this doesn’t work all of the time, if you want to say, “I wrote the letter in Okinawan” 沖縄語で手紙を書いた (Okinawa-go de tegami wo kaita). 沖縄口さーに手紙書ちゃん (Uchinaa-guchi saani tigami kachan). For one, さーに is an alternate version of っし, but, that isn’t the only thing. Okinawan doesn’t have a direct object particle (を in Japanese). In older literary works it was ゆ, but it no longer used in casual speech. Introducing yourself in Okinawan is interesting for a few reasons as well. Let’s say you were introducing yourself to a group. In Japanese you’d say みんなさこんにちは私はフィリクスです (Minna-san konnichiwa watashi ha Felixdesu) ぐすよー我んねーフィリクスでぃいちょいびーん (Gusuyoo wan’nee Felix di ichoibiin). Okinawan has a single word for saying ‘hello’ to a group. It also showcases the topic marker for names and other proper nouns. In Japanese there is only 1, は but Okinawan has 5! や, あー, えー, おー, のー! So, how do you know which to use? Well, there is a rule, typically the particle fuses with short vowels, a → aa, i → ee, u → oo, e → ee, o → oo, n → noo. Of course, the Okinawan pronoun 我ん, is a terrible example, because it is irregular, becoming 我んねー instead of 我んのー or 我んや. Yes. Like Japanese, there are numerous irregularities to pull your hair out over! I hope that this has been interesting for those who have bothered to go through the entire thing. It is important to discuss these languages because most Ryukyuan languages are either ‘definitely’ or ‘critically’ endangered. Mostly due to Japanese assimilation policies from the Meiji period onward, and World War 2. The people of Okinawa are a separate ethnic group, with their own culture, history, poems, songs, dances and languages. It would be a shame to lose something that helps to define a group of people like language does. I may or may not look in the Kyūshū dialects of Japanese next time. I’unno, I just find them interesting.

-

hrejs liked this · 2 weeks ago

hrejs liked this · 2 weeks ago -

floppydiskorigami liked this · 3 weeks ago

floppydiskorigami liked this · 3 weeks ago -

riddlersbimbo reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

riddlersbimbo reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

lokimesideways liked this · 2 months ago

lokimesideways liked this · 2 months ago -

boudicas-saphic-cbt liked this · 3 months ago

boudicas-saphic-cbt liked this · 3 months ago -

thermaphilia reblogged this · 3 months ago

thermaphilia reblogged this · 3 months ago -

thermaphilia liked this · 3 months ago

thermaphilia liked this · 3 months ago -

notadragon liked this · 4 months ago

notadragon liked this · 4 months ago -

inbetweensunkisses liked this · 5 months ago

inbetweensunkisses liked this · 5 months ago -

lucyinthedawn reblogged this · 5 months ago

lucyinthedawn reblogged this · 5 months ago -

dreamers-queen reblogged this · 6 months ago

dreamers-queen reblogged this · 6 months ago -

corvidcantina liked this · 7 months ago

corvidcantina liked this · 7 months ago -

crunchylion liked this · 7 months ago

crunchylion liked this · 7 months ago -

frejasr liked this · 8 months ago

frejasr liked this · 8 months ago -

ofoceanandwaves liked this · 8 months ago

ofoceanandwaves liked this · 8 months ago -

boo-keeper reblogged this · 8 months ago

boo-keeper reblogged this · 8 months ago -

boo-keeper liked this · 8 months ago

boo-keeper liked this · 8 months ago -

brown-aes-sedai reblogged this · 8 months ago

brown-aes-sedai reblogged this · 8 months ago -

darklycola liked this · 8 months ago

darklycola liked this · 8 months ago -

biichama reblogged this · 8 months ago

biichama reblogged this · 8 months ago -

biichama liked this · 8 months ago

biichama liked this · 8 months ago -

kirkfanatic liked this · 8 months ago

kirkfanatic liked this · 8 months ago -

kintotech reblogged this · 8 months ago

kintotech reblogged this · 8 months ago -

abandoned-as-mustard reblogged this · 8 months ago

abandoned-as-mustard reblogged this · 8 months ago -

abandoned-as-mustard liked this · 8 months ago

abandoned-as-mustard liked this · 8 months ago -

dreamers-queen reblogged this · 8 months ago

dreamers-queen reblogged this · 8 months ago -

theproblemwithsports liked this · 9 months ago

theproblemwithsports liked this · 9 months ago -

bigtrashfire reblogged this · 9 months ago

bigtrashfire reblogged this · 9 months ago -

bigtrashfire liked this · 9 months ago

bigtrashfire liked this · 9 months ago -

ankewehner liked this · 9 months ago

ankewehner liked this · 9 months ago -

doriandangerous reblogged this · 9 months ago

doriandangerous reblogged this · 9 months ago -

doriandangerous liked this · 9 months ago

doriandangerous liked this · 9 months ago -

spiderweb-wine reblogged this · 1 year ago

spiderweb-wine reblogged this · 1 year ago -

cerezo-de-jacaranda liked this · 1 year ago

cerezo-de-jacaranda liked this · 1 year ago -

rohzzzzz reblogged this · 1 year ago

rohzzzzz reblogged this · 1 year ago -

maxiel-tragic liked this · 1 year ago

maxiel-tragic liked this · 1 year ago -

orbydaz liked this · 1 year ago

orbydaz liked this · 1 year ago -

royalnow liked this · 1 year ago

royalnow liked this · 1 year ago -

wisepersonamuffinhorse liked this · 1 year ago

wisepersonamuffinhorse liked this · 1 year ago -

reinedeslivres liked this · 1 year ago

reinedeslivres liked this · 1 year ago -

spooks75 liked this · 1 year ago

spooks75 liked this · 1 year ago -

regencylady1810 reblogged this · 1 year ago

regencylady1810 reblogged this · 1 year ago -

mylazydog liked this · 1 year ago

mylazydog liked this · 1 year ago -

yia67 reblogged this · 1 year ago

yia67 reblogged this · 1 year ago -

dflogerzi liked this · 1 year ago

dflogerzi liked this · 1 year ago -

trexalicious reblogged this · 1 year ago

trexalicious reblogged this · 1 year ago -

amazon-anon liked this · 1 year ago

amazon-anon liked this · 1 year ago

A reblog of nerdy and quirky stuff that pique my interest.

291 posts